Armor: Chemistry and Physics

One of the big mistakes in assessing tanks is judging the defensive capability based on inches (or milometers) of armor. Armor is not armor and I'm going to go through some of the chemistry and physics of different types of armor in an attempt to enlighten people on what difference different types of armor mean.

First, let's examine three basic types of tank construction in WWII.

1) Bolted Armor

2) Welded Armor

3) Cast Armor

Bolted armor involves some kind of steel chassis with armored plates bolted on. This is the earliest type of armor and was popular with procurement because it was tested and was the most easy to repair. It required little metallurgical skill to shape and build. If an armored panel failed, it could simply be unbolted and a new panel bolted in its place.

It is not, however, popular with crews, as bolts are weak points and could be compromised even by machine gun fire.

Rivets are similar, but are more difficult to exchange and marginally safer for the crew. They are also cheaper.

Welded armor depends on welds, rather than bolts and frames, to form the chassis of the vehicle.

Welded armor still has weakness at the joints, but lacks the vulnerability of bolts or rivets when struck by machine guns projectiles. However, it is more technically demanding and workmanship is premium in the creation of a good welded hull.

However, the strongest form or tank construction is the cast hull. Casting involves pouring steel into a mold, forming a (mostly) finished product. Early French tanks generally were of cast construction. Casting provides the strongest type of armor, but it vastly more expensive and difficult to create.

Most of the Sherman is cast armor.

You can tell the different types of tank apart because a bolted or riveted tank has pronounced rivets visible on the outside of the armor. Welded tanks have a boxy or angular look, but lack the rivets or bolts. Cast tanks have rounded edges.

Now, no tank is purely of one type of construction. In fact, the T-34 replaced a welded turret with a cast one later on in the war. For example, almost all gun mantlets are cast. Further, cast vehicles frequently have applique armor bolted or welded on.

A secondary consideration is whether the steel is rolled or not. Rolled homogeneous plate is the standard and when you see penetration numbers it is almost always the amount of rolled homogeneous plate. The process involves heating the steel and then pressing it between to rollers. This is kind of like making pasta in that it helps blend the ingredients and makes the pasta smooth throughout. Rolled armor is, however, more difficult to bend, making it good for flat surfaces but less useful for places where you need the steel to be malleable to fit on various parts of the tank.

Finally, there is face hardening, which makes the steel stronger and likely to shatter projectiles on impact, but also makes the steel somewhat brittle. This is bad because it causes spalling, where the interior of the tank's armor breaks away and flies around the interior of the tank, creating a bad tank driving environment.

First, let's examine three basic types of tank construction in WWII.

1) Bolted Armor

2) Welded Armor

3) Cast Armor

Bolted armor involves some kind of steel chassis with armored plates bolted on. This is the earliest type of armor and was popular with procurement because it was tested and was the most easy to repair. It required little metallurgical skill to shape and build. If an armored panel failed, it could simply be unbolted and a new panel bolted in its place.

| The Pz38t (or LT38) is an example of a bolted armor tank. |

Rivets are similar, but are more difficult to exchange and marginally safer for the crew. They are also cheaper.

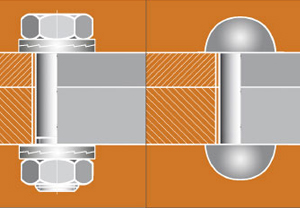

|

| Bolt vs. Rivet |

Welded armor still has weakness at the joints, but lacks the vulnerability of bolts or rivets when struck by machine guns projectiles. However, it is more technically demanding and workmanship is premium in the creation of a good welded hull.

| The Hetzer is an example of a welded armored vehicle. |

Most of the Sherman is cast armor.

You can tell the different types of tank apart because a bolted or riveted tank has pronounced rivets visible on the outside of the armor. Welded tanks have a boxy or angular look, but lack the rivets or bolts. Cast tanks have rounded edges.

Now, no tank is purely of one type of construction. In fact, the T-34 replaced a welded turret with a cast one later on in the war. For example, almost all gun mantlets are cast. Further, cast vehicles frequently have applique armor bolted or welded on.

A secondary consideration is whether the steel is rolled or not. Rolled homogeneous plate is the standard and when you see penetration numbers it is almost always the amount of rolled homogeneous plate. The process involves heating the steel and then pressing it between to rollers. This is kind of like making pasta in that it helps blend the ingredients and makes the pasta smooth throughout. Rolled armor is, however, more difficult to bend, making it good for flat surfaces but less useful for places where you need the steel to be malleable to fit on various parts of the tank.

Finally, there is face hardening, which makes the steel stronger and likely to shatter projectiles on impact, but also makes the steel somewhat brittle. This is bad because it causes spalling, where the interior of the tank's armor breaks away and flies around the interior of the tank, creating a bad tank driving environment.

Soviet analysis showed that the Royal Tiger's armor was susceptible to spalling, especially when hit by high explosives. In fact, the US Army would later develop a high explosive plastic round to specifically cause this kind of damage. I have never heard of Royal Tiger crews being afraid of this damage and the Soviet document said that it took two or three hits on the front glacis to cause this kind of damage, but it bears out that face hardening would, after a hit, make the vehicle more subject to spalling damage.

Obviously, you either have rolled or cast, you can't do both.

Later, I publish a quiz with armor type identifiers.

Comments